Writing as Healing

Writing as Healing

In this time of Shelter in Place, many of us have turned to gardening, baking, or writing to help us stay focused and grounded. I have done all of those things, but mostly I write. Writing is how I make meaning out of seemingly meaningless events, and journaling about Covid 19 and the fires recently surrounding me in California continues to serve that purpose.

I recently published a memoir about homesteading in the 1970s. When I am interviewed, or questioned after a virtual reading, I am often asked “How long did it take?” “What was your process?” “How did you remember all those details?” The answer? I began by freewriting.

Where to Start?

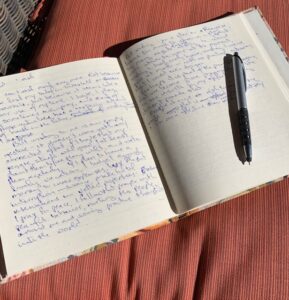

My first step was to select a journal that felt good in my hands, opened flat, and was lined. I wanted to use a physical journal to begin my memoir project because the process of writing connects our hands directly with our brains. If you are someone who likes to sketch, you might want to choose a journal that has both blank and lined pages. Drawing or doodling events from the past engages the creative side of your brain and can produce wonderful material that you can later write about.

Most writing happens in the frontal lobe. The problem is that this area of the brain is also responsible for reasoning and judgment, planning and problem-solving. Thus, when we write in the traditional way, we tend to edit our words as we write, telling ourselves we aren’t remembering the incident correctly, or are forgetting key elements, or – worse – that no one will be interested in what we write. Freewriting, on the other hand, increases the flow of ideas and reduces the chance that we’ll censor what we write. I begin each writing session with fifteen minutes of free writing.

Freewriting

The process is simple – put your pen on a page in your journal and start writing. If you have something specific in mind you’d like to write about, such as a childhood incident or a happy or sad memory, just start writing about it and don’t pick up your pen for at least five minutes. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or punctuation. Just write. If you start brainstorming a list of things to write about or touch on more than one memory in your free write, select one topic after five minutes, and go back to freewriting for another fifteen minutes. If you can’t think of anything to write, just keep repeating your subject (e.g., “Mama’s birthday,” or something like “I’m waiting for an idea to come, I’m waiting for an idea to come,” over and over until an idea comes. It works!).

Callum Sharp, of The Writing Cooperative, offers eight reasons why freewriting can also help us become better writers. These five relate directly to memoir writing.

Freewriting:

- builds confidence

- drives inspiration

- helps excavate emotional themes and barriers

- develops muscle memory and good habits

- generates honesty in your writing

This is how Ray Bradbury described freewriting: “Don’t think; just write!”

You don’t need to attend a memoir workshop or read a book about writing a memoir to freewrite. You don’t even need to join a writing group. Just find a comfy place to sit and an hour a day to reminisce and write down your memories. I did this for several years before I began to structure my memoir or to do any research. Then I began to dig into family history – photograph albums, birth, death, and marriage certificates, financial records, correspondence. I found a treasure trove of letters in a box with a ribbon around it, and it helped me decide what part of my life I wanted to write about. Because memoir is not a biography – it isn’t about your whole life, just a part of it that you want to explore and understand.

Memoir or Autobiography?

That is an important thing to remember about writing a memoir. Memoir is a process before it is a product. A memoir is a historical account written by you from personal knowledge or special sources. It’s a book about a sliver of your life, a collection of memories, the lessons learned, and key moments that shaped who you are. Written by you. It doesn’t start at your birth and end yesterday. Pick a time in your life when you were forced to change, and start writing about that time.

In order to narrow your focus, it can be helpful to list five life-changing events that you have experienced. They don’t have to be earth-shaking – just life-changing. For example, I took higher math classes in high school because I liked boys. The life-changing part was when I realized I actully liked math. Perhaps someone took you to a sushi bar for the first time against your wishes and you discovered that you loved sushi. If you’re over sixty, you probably remember where you were when President Kennedy was shot. Most of us alive today still remember where we were when the airplanes flew into the World Trade Center. Each of those events was a life-changing experience.

What stories do you want to share? Brainstorm from five to ten events in your life that had some kind of significance. They may or may not be related to the life-changing events you listed above. For example, a life-changing event might be the inauguration of President Kennedy, but your personal story might be about waving a tiny American flag as you stood in the freezing sleet with your sixth-grade class as Kennedy’s arcade made its way down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Select one of these ideas, and spend the rest of your hour writing about that event. Don’t judge yourself, or worry about grammar, spelling, or how many adverbs you’ve used. Just write. Then do it again the next day. And the next.

Do Your Homework

No one writes an entire memoir without doing some research, and eventually, you will want to do some also. Most of my source material came from journals, photo albums, old Christmas Card lists, and boxed-up letters from friends and lovers. But there are other sources of contemporary information you want to consider as well.

Did you or your parents save newspapers or magazines depicting important events? Keep diaries? Did you make memory boxes that contained the orchid corsage you wore to Senior Prom or the tickets to Phantom of the Opera at the Majestic Theater in New York? Do you keep receipts and other financial records beyond the required five years? Do you have access to birth, death, or marriage certificates, or membership in Ancestry.com? (if not, you might want to get one). Review the story you wrote during the last hour – where will you go to find background material or facts to make that particular story more interesting?

Leave a blank page in your journal then list every resource you can think of that might provide insights, details, memories. Leave another blank page and start to think about who shared these events with you.

Who can you talk to who might help you remember details or who know details that you never knew?

Are you still in touch with any of those sixth graders who flew with you to Kennedy’s Inauguration? Do you still communicate with the friend who double-dated with you to the Senior Prom? The ex-boyfriend who took you to Phantom (or his children)? How about Great Uncle Fred who seems like he’s going to live forever – what stories can he tell you about yourself at family gatherings? Does he know anything that you can use in one of your stories? Start making notes on your blank pages about who you can call or write or email to get more substance for your stories.

A true example from my memoir about homesteading: I was describing putting in a water line. The ride-on ditch digger my husband used had a quirky name, but I couldn’t remember it. I called an old friend who had been helping that day and asked if he remembered what it was called. He immediately came up with the name: Ditch Witch, and we had a wonderful conversation going down memory lane, unearthing several other details that I had forgotten.

By working just an hour a day, you will soon build a collection of stories. Each time you open your journal you’ll discover fresh ideas and resource material to add to your lists or to write about. Eventually, you may want to lengthen the time you spend writing or limit your sessions to three days a week, or two, or even one. The most important things are (1) You have made a start, and (2) Keep writing.

Once you have a reasonable body of work, it is time to start studying the memoir form, how to add interesting details, dialogue, and historical background. You can’t go wrong starting with Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life by Anne Lamott. Read memoirs, several of them. Some of my favorites are Me Talk Pretty One Day, by David Sedaris; Slouching Toward Bethlehem, by Joan Didion; Just Kids, by Patti Smith and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Wall. Once you’ve done that, you might want to find a memoir critique group — many now meet virtually — and begin to share pieces of your story for feedback. Enjoy the journey!

Have you written a memoir or want to? Read a memoir that you loved? Please share your personal memoir experience in a comment below. Let’s have a conversation!

Marlene Bumgarner moved to the California coast when her first grandchild was born and still lives there with her Border Colli, Kismet. The author of The Book of Whole Grains, Organic Cooking for (not-so-organic) Mothers, and Working with SchoolAge Children, Marlene has recently written a memoir about raising children, animals and vegetables on a rural plot of land in the 1970s, Back to the Land in Silicon Valley.

Note: This article first appeared as a guest post in 60 and Me.

Share this post

Great advice, beautifully written. Free writing was such an important thing for me to learn about (thanks, Laura Davis). Thank you for another great blog post.

Thank you, Joyce! I appreciate your kind words. Marlene

Hi Marlene! I remember using the Ditch Witch, too. I’ve enjoyed reading Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life by Anne Lamott, Me Talk Pretty One Day, by David Sedaris and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Wall.

I’ll have to read the other two you mentioned. I also really enjoyed reading all of Bailey White’s books. A friend brought them and also several Lamott books to me when I was in the hospital for 15 days.

I use the Bird by Bird message (just start and do one thing and then the next) and also another from Operating Instructions: left foot, right foot, left foot: breathe as my personal daily mantras!

Della

“Song is the language our soul understands most fluently.”

-Beth Moore

So many things we have in common! Write on . . . Marlene

Dear Marlene, thank you so much for posting how to go from free writing to manuscript. I’m a writer, too, and have been writing all of my life. Eventually took night classes in writing at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. Unfortunately, I have been going through a mental block. Reading what you wrote really hit home for me–and I think I’ll be able to begin writing once again. Thank you again! You’re a very special person! Sincerely, Dorothy

Thank you, Dorothy. I’m delighted that my essay was useful to you. By the way, I took my first creative writing class (in 1966) at CSM. Go Bulldogs! Marlene

Dorothy, You might find it helpful to join Meetup if you’re not already a member, and sign up to join a Shut Up and Write group in your area (or actually anywhere in the world as long as we’re meeting online). I have found that a very helpful way of keeping myself on track – the participants check in with one another, tell what they plan to work on, and then proceed to “shut up” and “write.” Some groups meet again at the end of two or three hours to see how people did.

Thank you for telling us about how you wrote your memoir. It let me know I’ve been doing it right! About, 3 year ago, I started writing snippets of my thoughts about certain moments in my life. You’ve let me know, I am doing it right! but I cannot write in handwriting; being a journalist for so many years, I have to write on the computer. That works for me. I keep all the printouts in a My Writings file folder. I actually started writing these mini-essays to let my children know about my life and thoughts. I have often forwarded them one at a time to my oldest son (who is now 55). I want my children know how my life developed. After reading your marvelous memoir, I am encouraged to keep writing!

Hi, Donna. Many people find that writing on the computer works for them – I do sometimes write on my iPad. Whatever works for you.

Thanks so much for your comments. Marlene